How much of an asset is experience of warfare to a future political career? Does a spell in the army, navy or air force, particularly during a world war always lead to popularity? Is it any use whatsoever in helping leaders make decisions once in power?

Winston Churchill’s long record of military heroism probably made him the ideal person to lead Britain through the darkest days of the Second War. But in the Thirties, when Churchill was in the political wilderness and appeasement was in vogue, Churchill’s background probably counted against him. Coupled with his warnings about Nazi rearmament, Churchill’s reputation fuelled fears that he was a warmonger. His role in the disastrous Gallipoli landings in 1915 complicated matters still further. Churchill had resigned as Lord of the Admiralty and immediately volunteered for the Western Front. He was the first of four Great War veterans to lead Britain.

If ever a man had cause to hate war, it was Churchill’s successor Sir Anthony Eden. He had not only fought in the First World War but lost two brothers in the conflict as well as a son in World War II. But Eden recognised the dangers of appeasement (before World War II) and resigned as Foreign Secretary over Neville Chamberlain’s friendliness towards Mussolini in the late Thirties. It could have been the end of a promising career for Eden. However, with the outbreak of war, like Churchill, his arguments seemed vindicated. He returned, eventually succeeding Churchill in 1955.

Sadly as Prime Minister, Eden’s instincts served him less well. Perhaps viewing the Egyptian leader Nasser as a new Il Duce, Eden led Britain into a disastrously ill conceived attempt to retake the Suez Canal in 1956. The end result was a calamitous humiliating withdrawal and Eden’s downfall.

Both Clement Attlee and Harold Macmillan served in the First World War too as did the US Presidents Harry S Truman and Dwight “Ike” Eisenhower. The impact of the Great War on their leadership isn’t obvious. But for Ike, his major role as Commander of the Allied Forces in Europe in the Second World War was to prove crucial to his election.

General Eisenhower had never been elected to any office before 1952 and his huge fame and popularity as a General at a time of Cold War in Europe and hot war in Korea was almost the sole basis for his 1952 presidential campaign. He won handsomely then and in 1956, both times beating the less charismatic Adlai Stevenson comfortably.

But Ike was only the first of seven World War II veterans to make it to the White House between 1953 and 1993. Some were more heroic than others. John F. Kennedy had rescued the crew of his Japanese PT 109 swift boat after the Japanese rammed it in the Pacific. Kennedy had swum dragging a colleague to safety while holding a lifeboat in his teeth. Ronald Reagan, in contrast, spent most of the war making propaganda films. But every leader for forty years was a WWII war veteran. The last one was George HW Bush. Like Senator Bob Dole who unsuccessfully sought the presidency in 1996, aged seventy three, Bush had been a pilot.

Oddly, although many notable British politicians served in World War II (for example, Denis Healey, Roy Jenkins, Tony Benn, John Profumo, Colditz escapee Airey Neave, William Whitelaw, Enoch Powell and many others) only two: Edward Heath and James Callaghan became Prime Minister. Neither seems to have gained much politically from their war experience. Callaghan relished anything to do with the navy. Heath spoke in later life over his unease over the execution of a Polish officer in 1945. But Callaghan never won a General Election and Heath only won one and lost three. Harold Wilson, in contrast, spent the war in the civil service but won four out of five General Elections.

Perhaps the issue was less relevant in the Britain of the Seventies or than in the US where the president is also Commander in Chief. But even there, the war was rarely a big issue other than in the case of Eisenhower or perhaps in helping Kennedy beat his Democrat rival Hubert Humphrey (who had not served in the war) in 1960. President Ford’s running mate Bob Dole (again) also committed a damaging gaffe in the 1976 Vice Presidential TV debates claiming that every 20th century war had been a “Democratic war” started by a Democratic president.

Margaret Thatcher was largely excused from any expectation of military service simply because she was a woman. Yet many women did do voluntary work during the war, joining the Wrens and such like. The young Margaret Roberts chose to focus on her career and Oxford instead. Thatcher was fortunate to escape serious scrutiny on this. Her Labour opponent in 1983, Michael Foot was less lucky. He had been unable to fight in the Second World War due to asthma (which bizarrely seems to have been cured buy a car accident in the Sixties) but in the jingoistic atmosphere after the Falklands War, both Foot’s championing of CND and even his choice of coat at the Cenotaph for the Remembrance Sunday service led his patriotism, entirely unfairly to be questioned.

Foot was born in 1913. His successor as Labour leader Neil Kinnock was actually born during the Second World War in 1942. In Britain, national service had ended with the Fifties. Only a few notable politicians have had military experience since the Eighties.

In the United States, the focus shifted from World War Two to the far more controversial legacy of Vietnam. In 1988, George HW Bush’s running mate Dan Quayle, already under scrutiny over his inexperience and competence, was found to have used his family’s connections to ensure enrolment on the Indiana National Guard twenty years before. The National Guard were traditionally seen as an easy escape route to avoid the draft. Quayle survived but his embarrassment contrasted him unfavourably with Colonel Oliver North, a leading figure in the Iran-Contra Scandal but a decorated Vietnam vet.

Four years later, the Democratic candidate Governor Bill Clinton saw his campaign descend into controversy when it was revealed he too had evaded the draft. But Clinton survived, perhaps helped by the fact, that unlike Quayle or George W. Bush later on, he had actually opposed the war. Bush’s joining of the Texas National Guard to avoid service was exacerbated in 2004, by the revelation that he had gone AWOL while even doing that at one point. Many assumed this to be drink related.

Bush’s opponent Democrat Senator John Kerry was well placed as regards Vietnam, having not only served there heroically but become a vocal opponent of the war on his return. Vietnam suddenly became a big issue again at the time of the Iraq war. But despite his strong position, Kerry overplayed the Vietnam card. Although the Republicans erred in attempting to fake a Seventies picture of a young Kerry supposedly standing next to fiercely anti-war activist Jane Fonda, and were not helped by Vice President Dick Cheney admitting he had avoided service too, claiming he had “other priorities”, Kerry’s overemphasis on his war record ultimately totally backfired.

In 2008, Barack Obama beat Vietnam vet and former Prisoner of War John McCain for the presidency. The 2012 election between Obama and Romney was the first since 1944 in which neither of the two main candidates had served in a world war or Vietnam.

Do war vets make better presidents? It seems doubtful. Neither Abraham Lincoln or Franklin Roosevelt served in the forces (FDR was already a politician during the First World War. He contracted polio in the Twenties). Were they thus automatically worse presidents than Richard Nixon or Jimmy Carter who did?

Eisenhower and Kennedy may have benefitted popularity-wise from their years of service. But did anyone else?

Every election between 1992 and 2008 was fought between a war veteran and a non-combatant:

1992: President George W Bush (WWII) Vs Governor Bill Clinton: Clinton won.

1996: Senator Bob Dole (WWII) Vs President Bill Clinton: Clinton won.

2000: Vice President Al Gore (Vietnam) Vs Governor George W. Bush. Bush won.

2004: Senator John Kerry (Vietnam) Vs President George W. Bush. Bush won.

2008: Senator John McCain (Vietnam) Vs Senator Barack Obama. Obama won.

As we can see, the non-combatant beat the veteran every time.

So far no Vietnam veterans at all have won the presidency yet this era may not be over yet.

In the UK, the only recent notable MPs with military backgrounds have been Paddy Ashdown, the Lib Dem leader between 1988 and 1999 and Iain Duncan Smith, Tory leader. It is true, Ashdown’s military background contributed to his popularity. But in the case of IDS, the least successful Opposition leader since the war, any advantage even during the Iraq War was extremely well hidden.

Ultimately, war experience may bring about good qualities and spawn great leaders, notably Churchill. But it is rarely a decisive factor in terms of popularity or leadership.

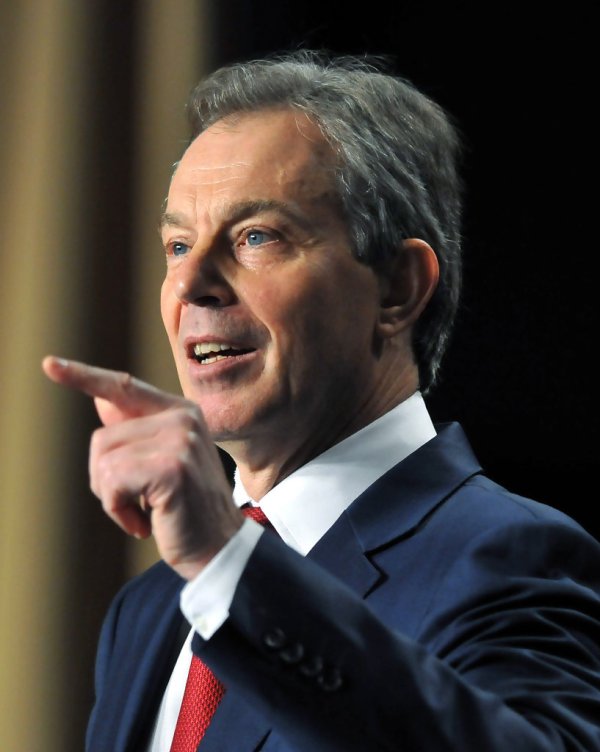

Some leaders such as Blair or Thatcher have proven natural leaders in peace and war without any military background at all. Others such as Sir Anthony Eden or Edward Heath found their military background little help in office and totally floundered in Downing Street.

Basically, if you are unsure who to vote for, basing your decision on the candidate’s military background is unlikely to help you to make the right decision.